United They Stand

Leeds and Grenville counties in perpetual battle to maintain, improve

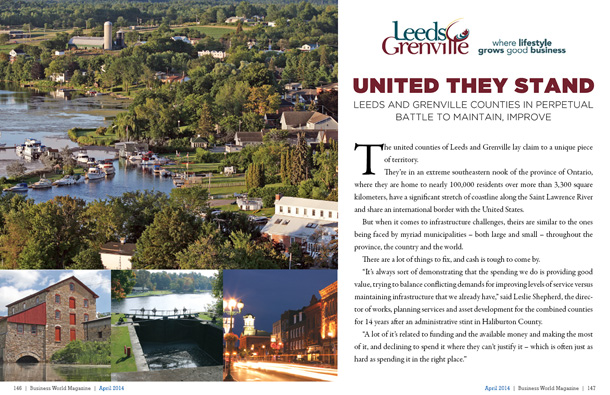

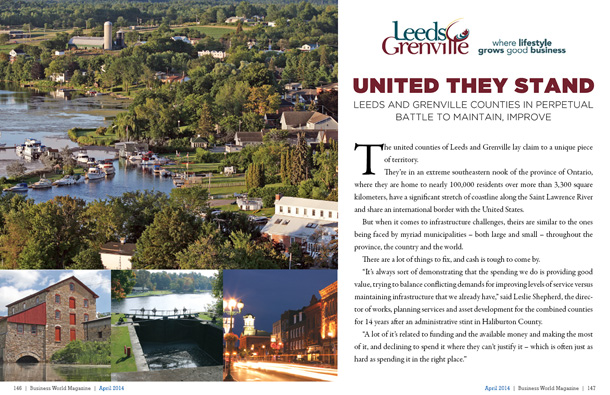

The united counties of Leeds and Grenville lay claim to a unique piece of territory.

They’re in an extreme southeastern nook of the province of Ontario, where they are home to nearly 100,000 residents over more than 3,300 square kilometers, have a significant stretch of coastline along the Saint Lawrence River and share an international border with the United States.

But when it comes to infrastructure challenges, theirs are similar to the ones being faced by myriad municipalities – both large and small – throughout the province, the country and the world.

There are a lot of things to fix, and cash is tough to come by.

“It’s always sort of demonstrating that the spending we do is providing good value, trying to balance conflicting demands for improving levels of service versus maintaining infrastructure that we already have,†said Leslie Shepherd, the director of works, planning services and asset development for the combined counties for 14 years after an administrative stint in Haliburton County.

“A lot of it’s related to funding and the available money and making the most of it, and declining to spend it where they can’t justify it – which is often just as hard as spending it in the right place.â€

The reality of growing need and shrinking resources pushes Shepherd and those in similar positions into the oft-perplexing task of having to prioritize which infrastructure needs are most pressing and which ones will have to wait until a more favorable funding climate develops.

It’s the sort of scenario he’s become accustomed to in a career of public service that began when he graduated from Queens University in nearby Kingston, Ontario in 1988, but it’s still not easy.

“What we’re trying to do, and it’s done fairly subjectively in a lot of ways, is look at the value based on how many users there are,†he said. “On roads, for example, higher-traffic roads get priority over lower-traffic roads. On lower-traffic roads, we will do sort of a holding strategy or an expanded maintenance program to just keep them going so we can spend the money on the higher-traffic roads.

“There are very important roads, there are somewhat important roads and there are roads that only serve a few people. Bridges are a little different because you have to keep them in a certain condition or they’re not safe, but certainly we try to spend more money on the busier roads.

“It’s almost axiomatic, but the term bang for the buck applies. If 10,000 people hit a bump on a busy road, or 1,000 people hit a bump on a less-busy road, which is preferable? It’s a pretty straightforward concept, but how you do it can get quite complicated if you let it.â€

Still, while the nature of the work puts a lot of public works people and asset managers in a constant state of planning for future needs and projects, Shepherd said the relatively flat growth in Leeds and Grenville over the years has taken away some of the need for a constant future focus.

The combined population in the counties was 96,206 according to the 2001 census, skipped up 2.7 percent to 99,206 in the 2006 census and upticked just a tenth of a percent to 99,306 in 2011.

It doesn’t mean the job is easy, Shepherd said, but perhaps easier than it could be.

“There’s no population growth and traffic growth is quite modest, so in those situations we’re just renewing what we have,†he said. “We don’t have a need to upgrade capacity. If it’s a secondary highway, it’s going to be a secondary highway for decades.

“In one corner where we’ve got some more significant growth, we’ve done some more forward looking and we’ve been working on a roundabout corridor for maybe 10 years. That would be much longer-range planning than we’re doing for the most part.â€

The day-to-day public works program for the counties’ roads involves periodic resurfacing and rehabilitation on the pavements and an ongoing assessment of the inventory of 120 bridges and large culverts. All 120 are inspected every two years and anything that’s identified as in need of repair, or in need of eventual replacement, is put on a list that’s updated every two years.

A “fairly-detailed†10-year plan exists for road and bridge renewal, Shepherd said, and one particular area of the county near Kemptville – which is home to four elementary schools, two high schools, three parks and two hotels – is the source of much of the long-term growth the county anticipates.

A stretch of road in that area is being looked at for possible expansion to four lanes, and officials closely monitor traffic growth and generate detailed estimates on road conditions and required upgrades whenever a significant residential or commercial development is initiated.

“That’s really the only area of the county that’s pushing us that way,†Shepherd said. “It’s nice in a sense because we know where we are and what our needs are, and we’re not bouncing all over. Still, it’s a bit of a balancing act. There are 10 regional representatives and they all need to see some action in their own neighborhoods, so we get a bit of a balancing act.â€

Aside from the bureaucracy issues, Shepherd and his team have another persistent foe: weather.

The combined county seat of Brockville receives measurable snowfall in eight of 12 months each year, on average, and the temperature veers from an average high of 25.6 degrees in July to minus-3.9 in January, with average lows dipping to minus-12.5 in January as well.

Brockville averages more than 44 days per year with at least two-tenths of a centimeter of snow, and its perpetual effect on the roads provides a never-ending challenge.

To combat Mother Nature, a whole series of standard approaches are implemented – including bracing manhole covers and other drainage items so they don’t move around due to frost heaving. Asphalt and concrete sealers and rejuvenators are also used to keep road surfaces as tight as possible and keep moisture out, which can scale down the amount of deterioration.

“The weather has as much wear and tear effect on a lot of the infrastructure as the traffic does,†Shepherd said. “In a lot of cases it’s frost-related, and de-icing materials over time have some effect on the bridges. A lot of the deterioration and the aging of the infrastructure is due to weather and the road salt as opposed to the traffic itself. The reason we end up doing rehabilitation is weather effects.

“It comes back to the balancing act and how you’re going to get the best bang for your buck. There’s no use putting down lots of pavement if it’s going to fall apart in five years. If you can seal it up and get it to not fall apart for an additional five years, you look at the cost benefit. The rejuvenator we use is maybe a dollar or two per square meter. The paving costs $10.

“You look at the cost-benefit and if it extends your life by 15 or 20 percent, it’s well worth it.â€

AT A GLANCE

WHO: United Counties of Leeds and Grenville

WHAT: Administrative union of counties since 1850 and home to 99,306 residents

WHERE: Southeastern Ontario, on an international border with the United States

WEBSITE: www.LeedsGrenville.com